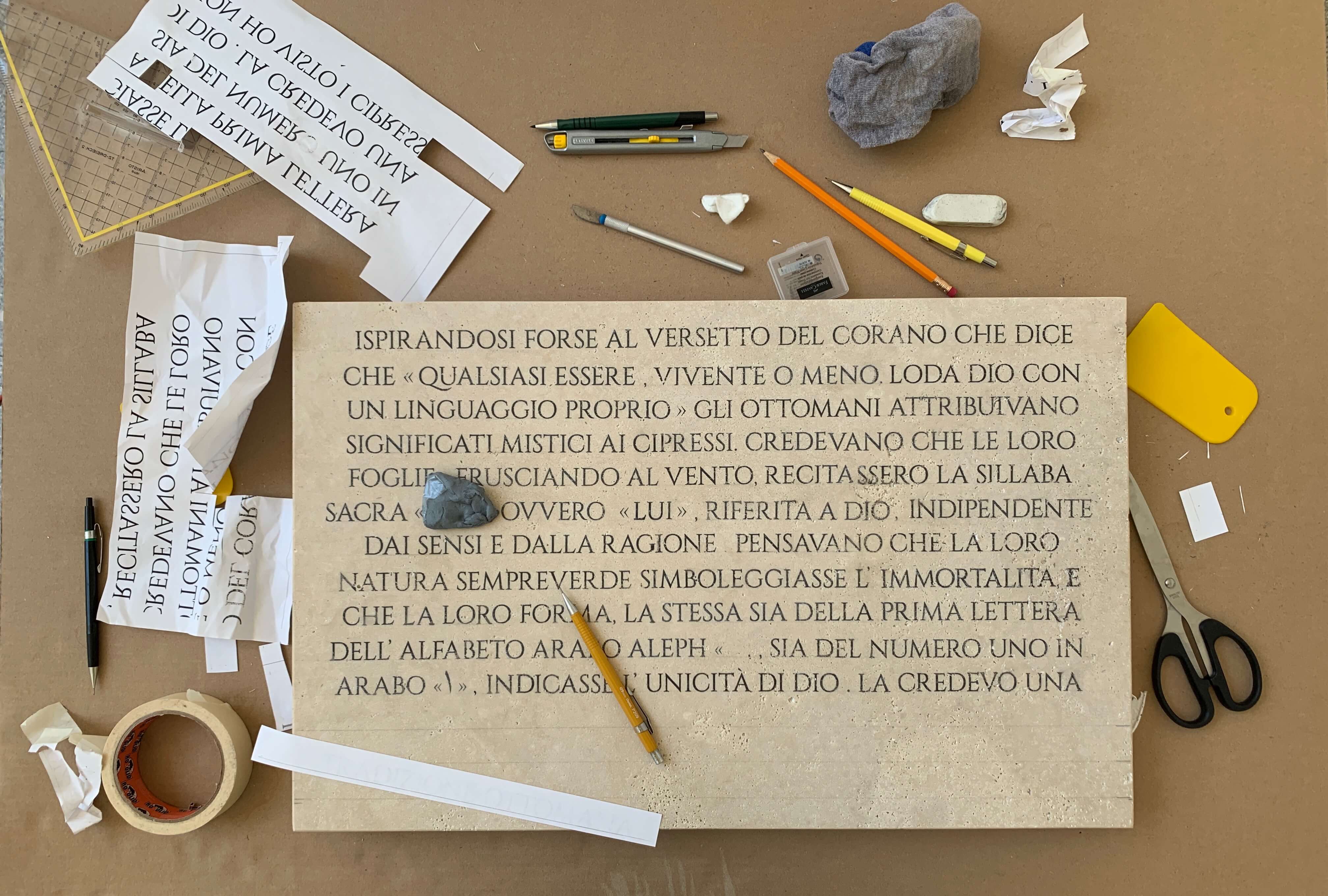

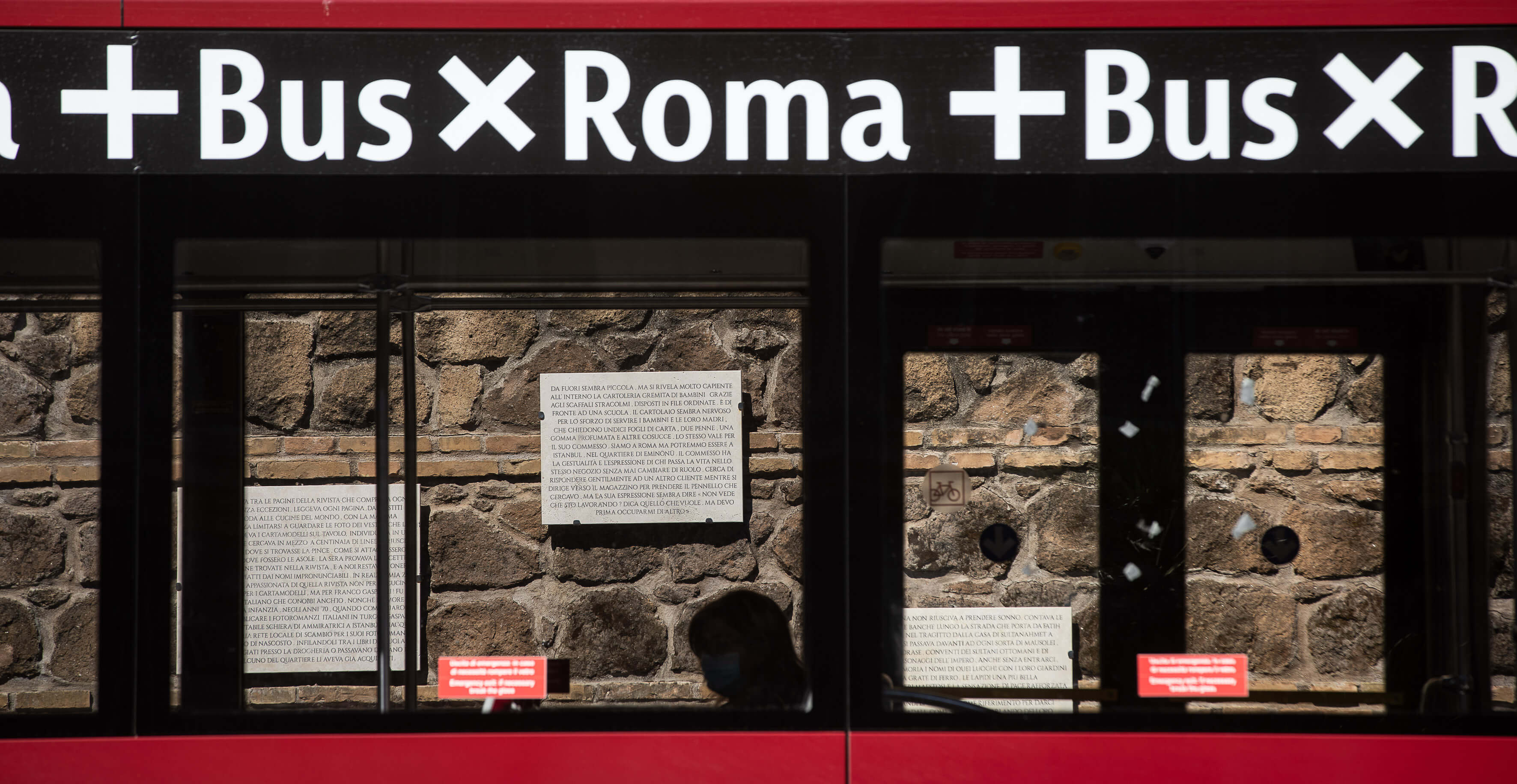

2020, Travertine tablets with ten original literature miniatures

Developed In the framework of the Art in Public Space Project: Villa Massimo Si Avvicina", Villa Massimo, Rome

| / |

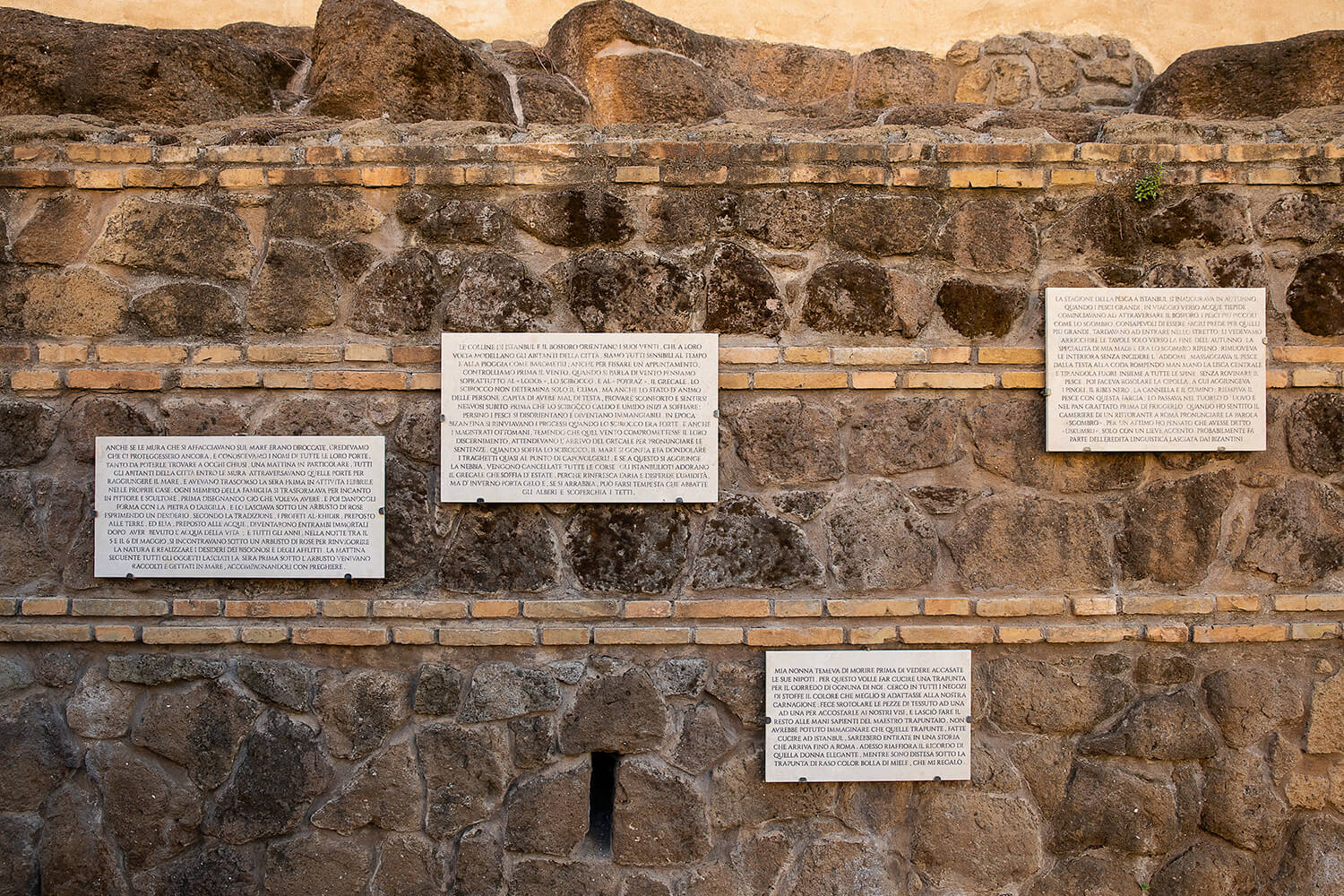

Her work consists of ten literary miniatures inscribed on tablets made of travertine, a material that is typical for Rome, that were exhibited on the external walls of the Villa Massimo grounds along the Viale XXI Aprile. “Le due Rome” also alludes to the eponymous Le due Rome: Confronto tra Roma e Costantinopoli penned by the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras, who taught widely in Venice and Florence at the end of the 14th century. He significantly contributed to opening up antiquity’s cultural heritage, which hitherto had been preserved in Byzantine libraries, making it available to scholars of the early Renaissance. By dint of Chrysoloras’ efforts, the memory of a kinship between Rome and Constantinople was rekindled, which offered the humanism of the early Renaissance a vital impulse, thus playing a critical role in the modernizing thrust that was to impact the whole of Europe over the course of time.

Nowadays, two perspectives on Rome predominate. The first considers the city as a life-sized walk-in Wunderkammer of European culture and world history, overflowing with untold layers of stories and history, of symbols, relics and myth and texts. It’s regarded as a wellspring where the mythical potential from Eternal Rome’s most diverse epochs recompose themselves over and again, as they have repeatedly done down through the millennia.

The second perspective, closely intertwined with the first, views Rome as the nexus of global Catholicism. While accepted in the global North as part and parcel of its own history, it should be understood independently of it. In principle, this perspective is autonomous, given that for devout Catholics the world over, Rome, namely the Vatican, constitutes a prominent global reference point.

And yet, the Eternal City also happens to be a hub amidst the matrix of urban agglomerations scattered across the Mediterranean coastal region. In this close-knit network, Rome is but one city among others that resemble each other in multiple aspects, inter alia, urban and social practices, as well as the conditions and mindsets that emerged therefrom. These social structures, organized in a more relational fashion, call for a specific understanding of time. Local traditions and symbols, customs, tales of yesterday and bygone days are valued and carry sway throughout those societies whose collective memories also measure the passage of time in generations.

Le due Rome, today’s twin cities of Rome and Istanbul, form part of a highly cohesive cultural space, which, to date, has endured and whose essence consists of vibrant communication, close collaboration and trade links. By calling into question those national specificities used as elements in forging an identity, the identity-focused policies embraced by modern nation-states across the 19th and 20th centuries ultimately overshadowed the awareness of these common roots.

Ersen's Texts in the order of appearance on the wall, stone tablet from left to right:

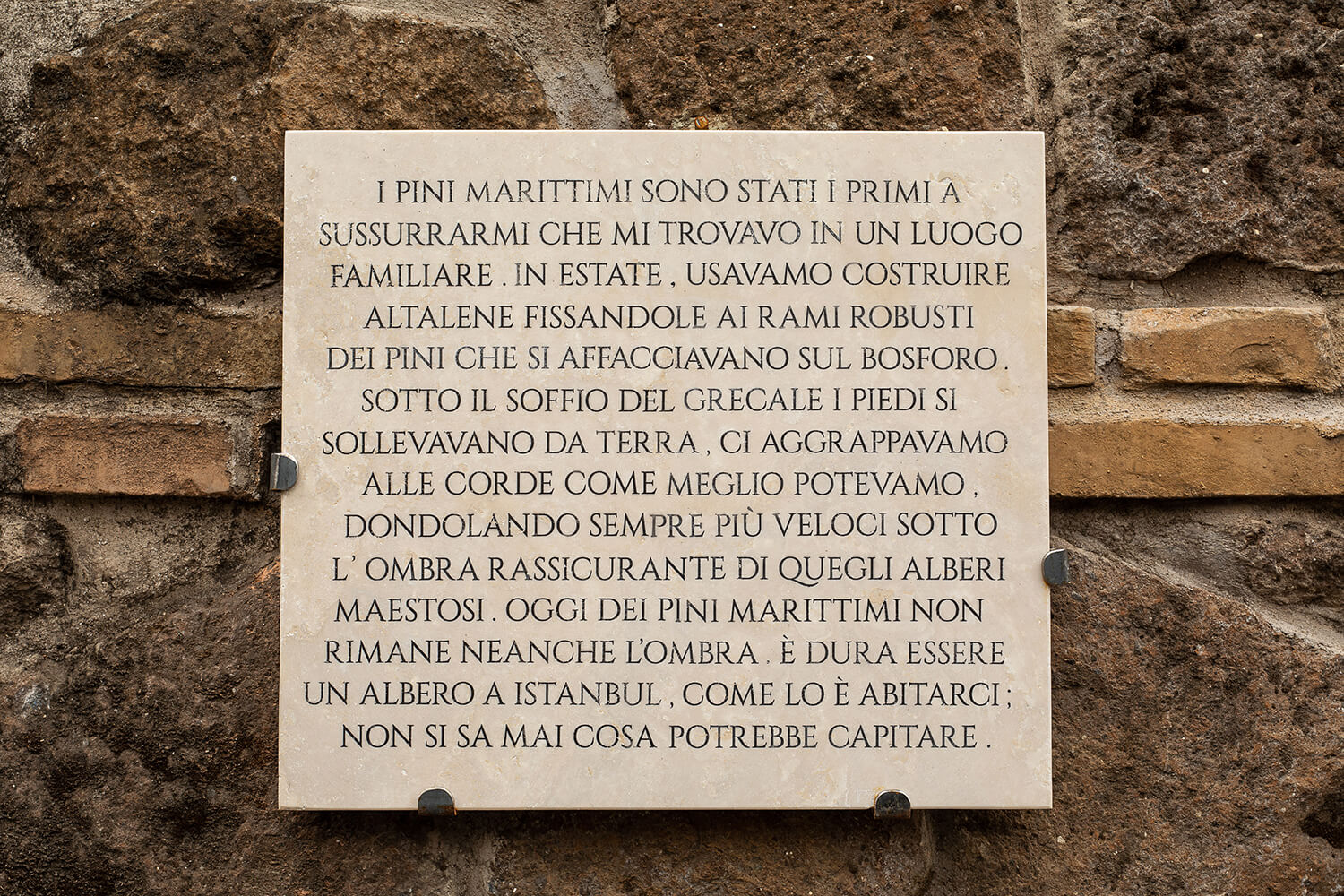

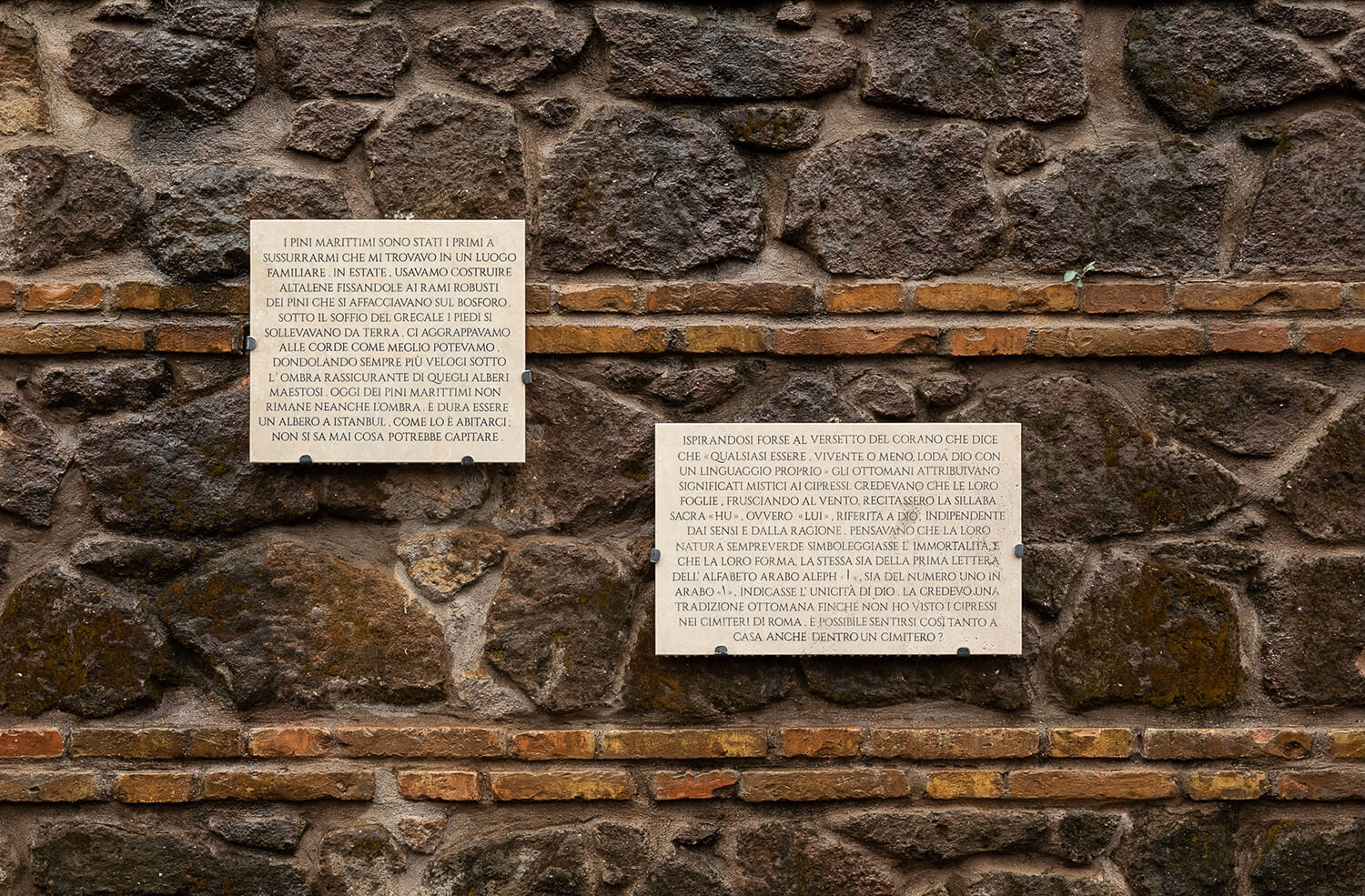

Pinie

The maritime pines were the first to whisper to me that I was in a familiar place. In summer, we used to build swings by fixing them onto the sturdy branches of the pines overlooking the Bosphorus. The Gregale would sweep us off the ground and we clutched onto the ropes as tightly as possible, swinging faster and faster under the reassuring shade of the caring branches of those majestic trees. Not a whiff of those maritime pines survives to this day. It is equally as hard to be a tree in Istanbul as it is to live there; you never know what might happen.

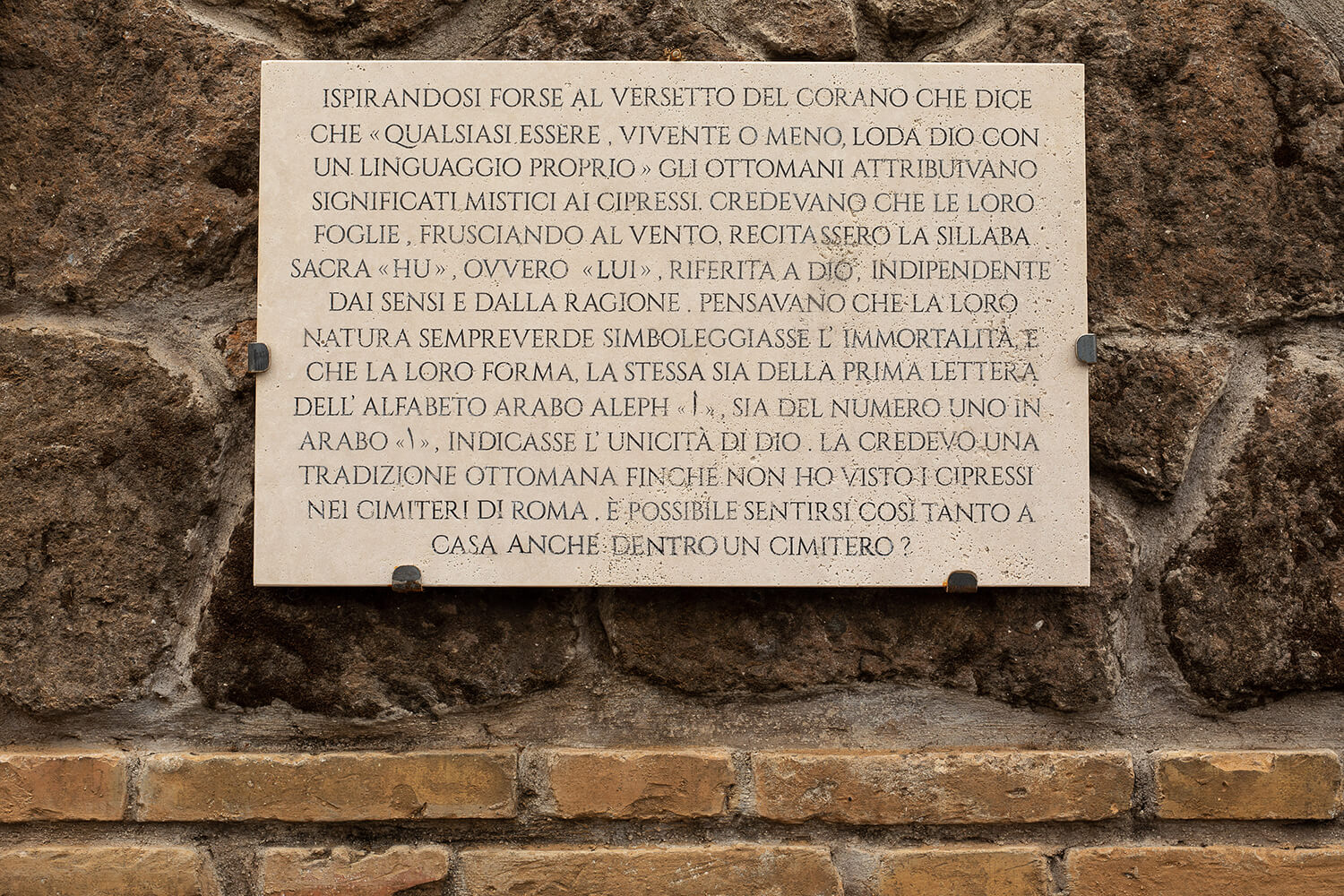

Zypresse

Inspired perhaps by that verse from the Qur’an that states: “All creation praises God, even if this praise is not in a human language,” the Ottomans attributed mystical qualities to cypresses. They believed that their leaves, as they rustled in the wind, recited the sacred syllable “Hu”, or “He”, referring to God, whose existence cannot be perceived by the senses nor fully acknowledged by pure reason. They thought that the evergreen cypresses nature symbolized immortality and that their shape, similar in form to both the first letter of the Arabic alphabet ảleph " ا " and the number one in Arabic " ١ ", indicated the oneness of God. I believed it to be an Ottoman tradition until the day I came across cypress trees in the cemeteries of Rome. Is it possible to feel so at home even amidst the gravestones?

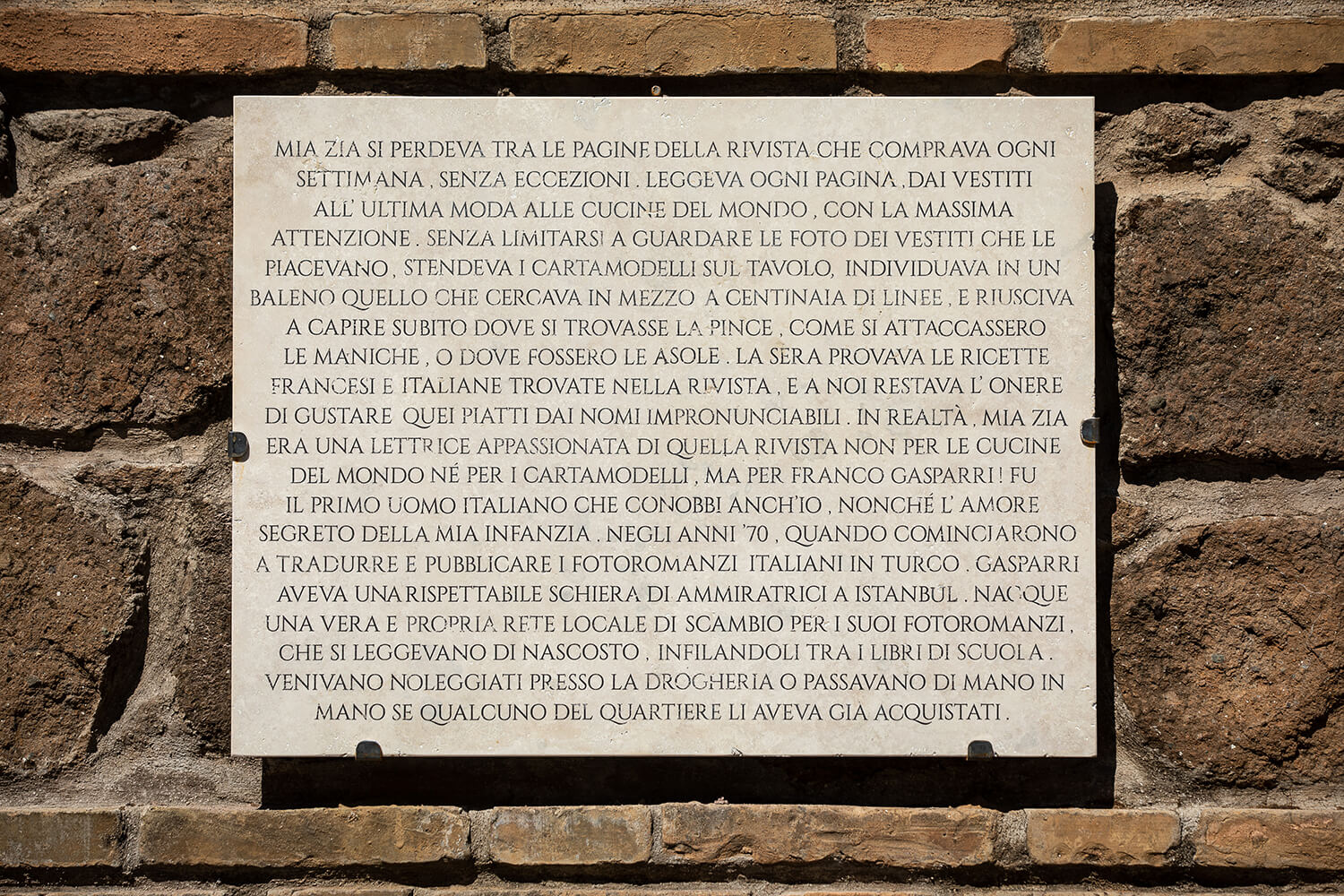

GASPARRI

My aunt would get lost amidst the pages of the magazine she used to buy week in week out, come rain or shine. Every single page was read, from the most fashionable clothes to world cuisines, with the utmost attention. She didn’t not just look at the pictures of those clothes that took her eye, but would lay out the patterns on the table, and within a heartbeat she found what she was searching amidst hundreds of lines: She could immediately grasp where the dart was, how to attach the sleeves, or where the buttonholes were. In the evenings she would experiment with those French and Italian recipes published in the magazine; we were left with the task of tasting those dishes with unpronounceable names. In truth, my aunt was an enthusiastic reader of that magazine not for world cuisines or patterns, the reason named Franco Gasparri! He was the first Italian man I became acquainted with, the secret love of my childhood –– something I never confessed to anyone. In the 1970s, when Italian photo novels began to be translated and published in Turkish, Gasparri built up a considerable following of female admirers in Istanbul. A local exchange network was created for his novels. Slipping them into schoolbooks, they were read in secret. They were either rented from the kiosk or passed around if someone in the neighborhood had already purchased them.

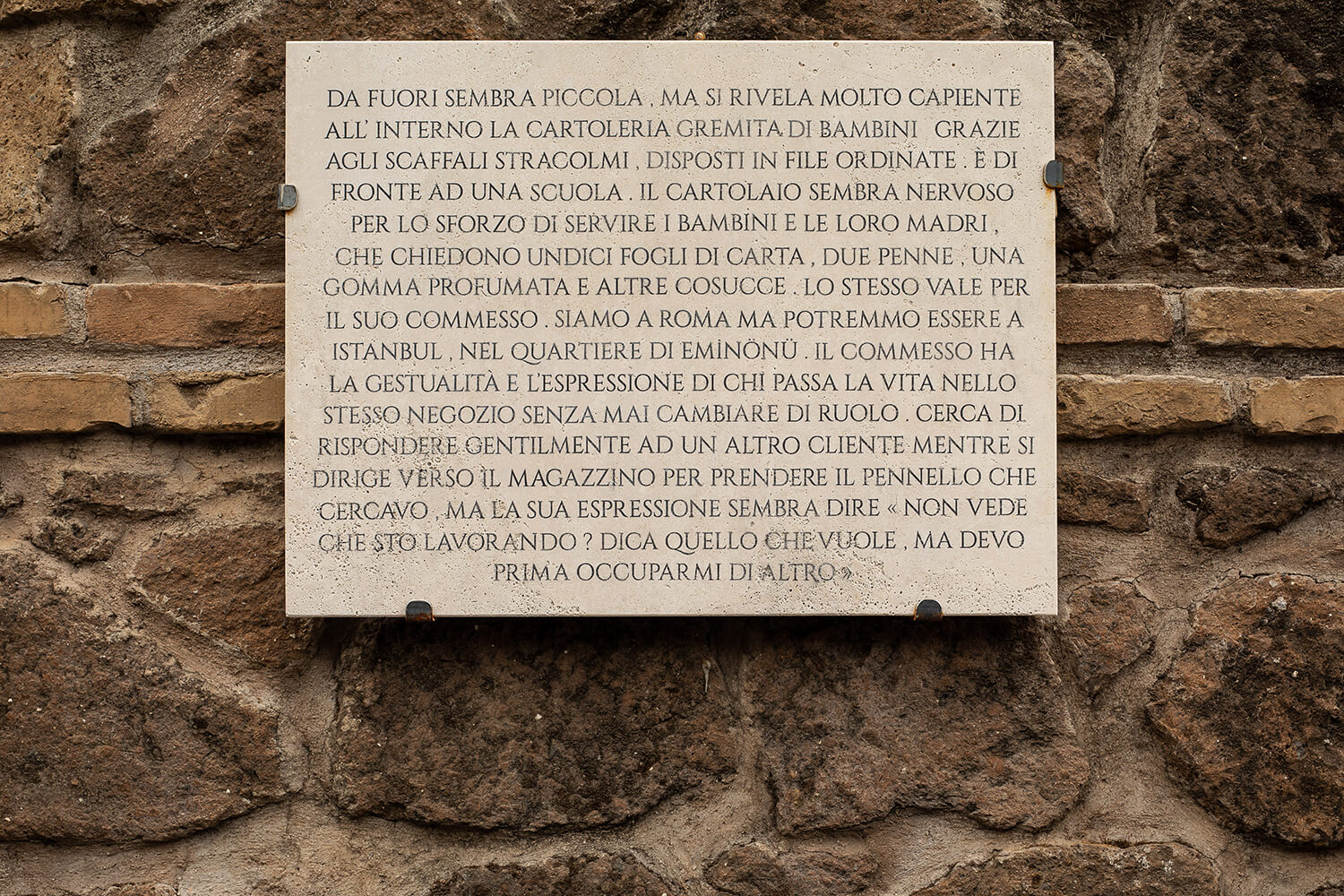

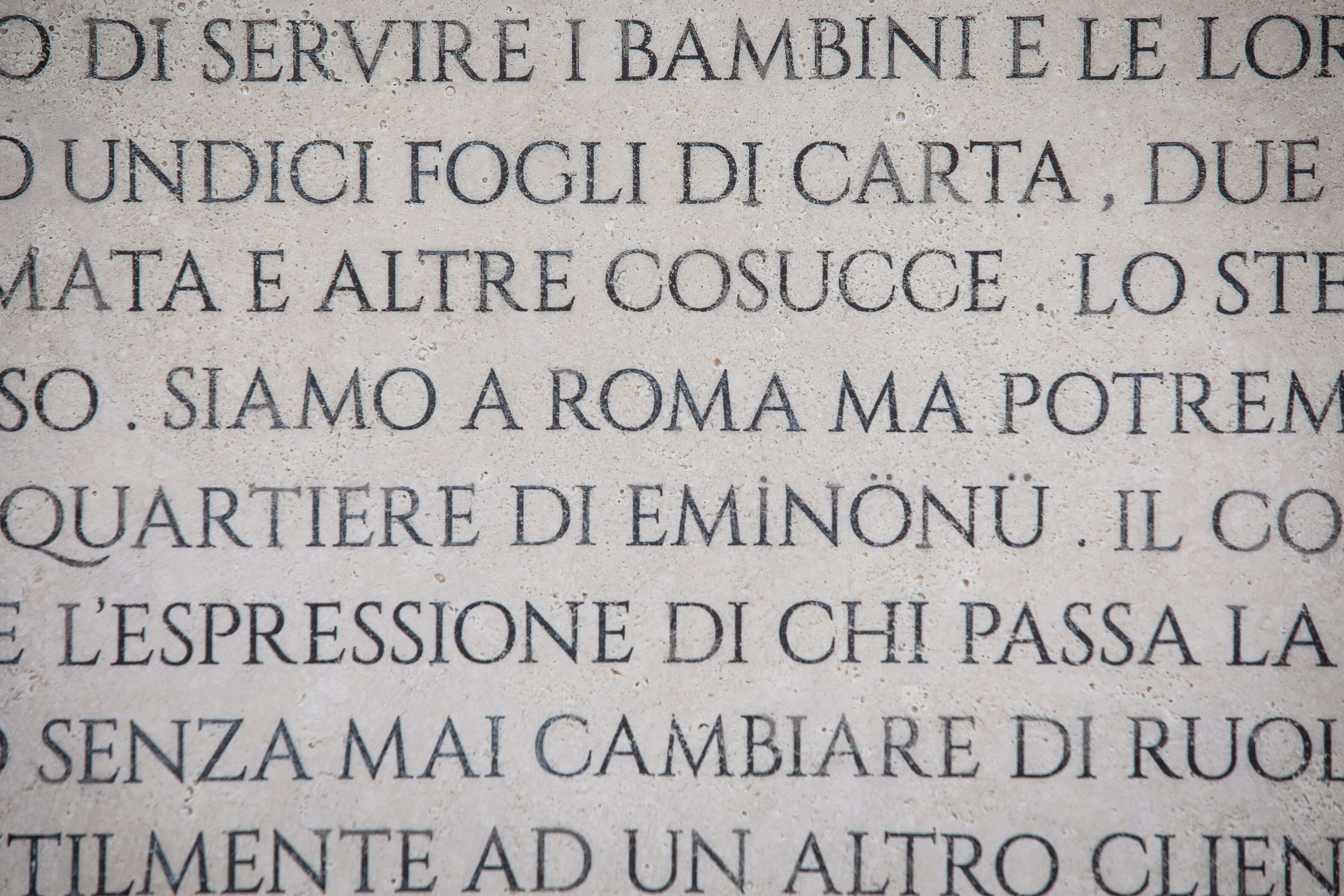

Stationery

Although it looks rather small from the outside, the stationery shop packed with children turns out to be very spacious inside, thanks to its crammed shelves arranged in neat rows. It faces a school situated right across the street. The stationer seems rather nervous due to the strain of serving the children and their mothers, who ask for eleven sheets of paper, two pens, a scented rubber and other similar knick-knacks. The same goes for his shop assistant. We are in Rome, but we might very well be in Istanbul, in the Eminönü neighborhood. The assistant’s gestures and facial expressions bespeak of a lifetime spent in the same shop without ever changing his role. Though he tries to respond politely to another customer on his way to the stock room to get the paintbrush I was looking for, his expression seems to say: “Can't you see I'm working? Tell me what you need, but I’ve something else to do first.”

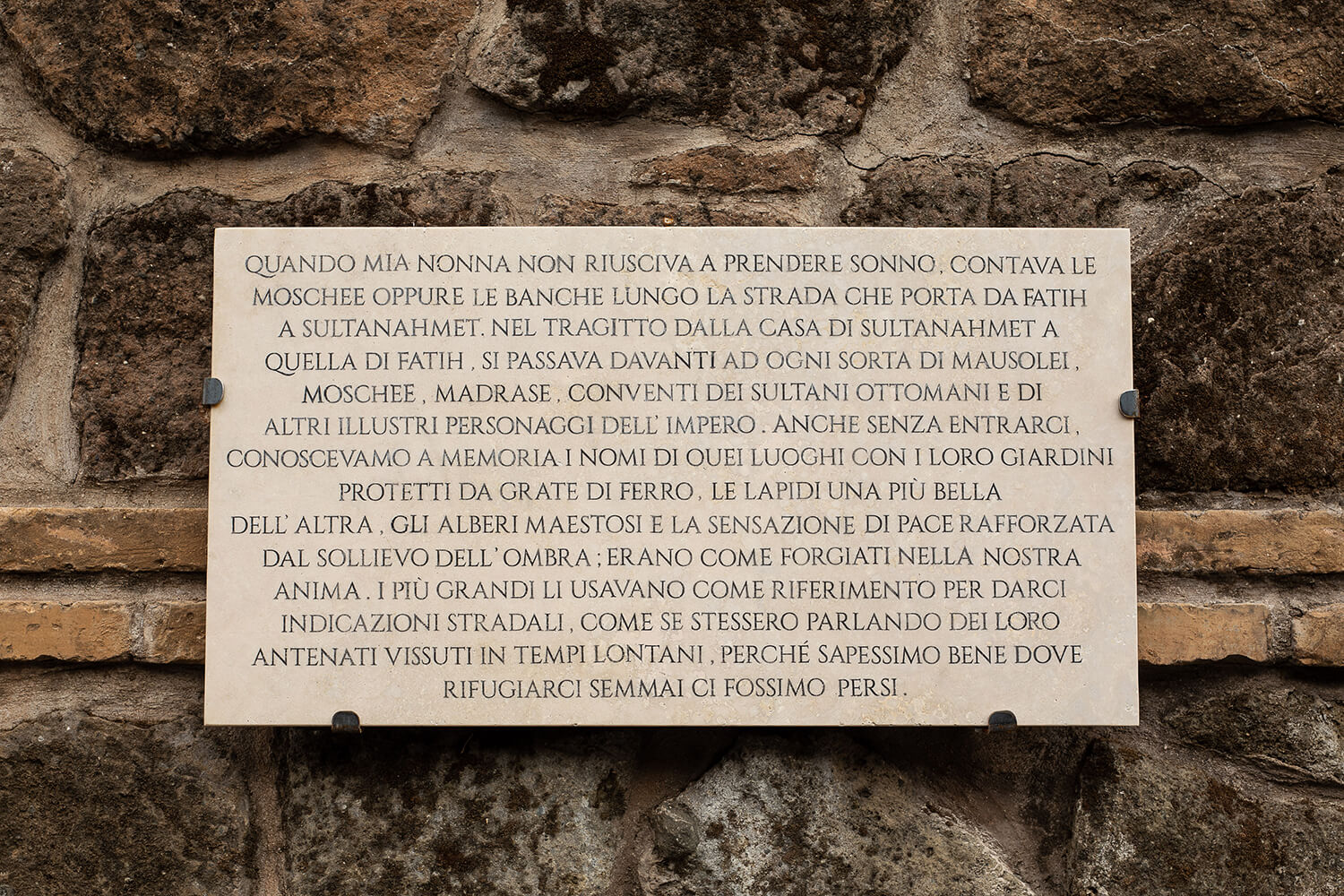

Fatih

Whenever my grandmother had trouble falling asleep, she would start counting the mosques or banks along the road leading from Fatih to Sultanahmet. On the way from the house in Sultanahmet to the one in Fatih, we used to walk past all sorts of mausoleums, mosques, madrasas, monasteries of the Ottoman sultans and other prominent figures of the Empire. Even without stepping inside, we knew their names by heart, with iron grates protecting their gardens protected, their tombstones one lovelier than the next, their majestic trees and that feeling of peace enhanced by the sense of relief provided by the shade: We felt as if they had been forged into our souls. The family’s elder members used them as a reference when giving us directions, as though talking about their ancestors who lived in distant times, so that we would know where to go if we ever got lost.

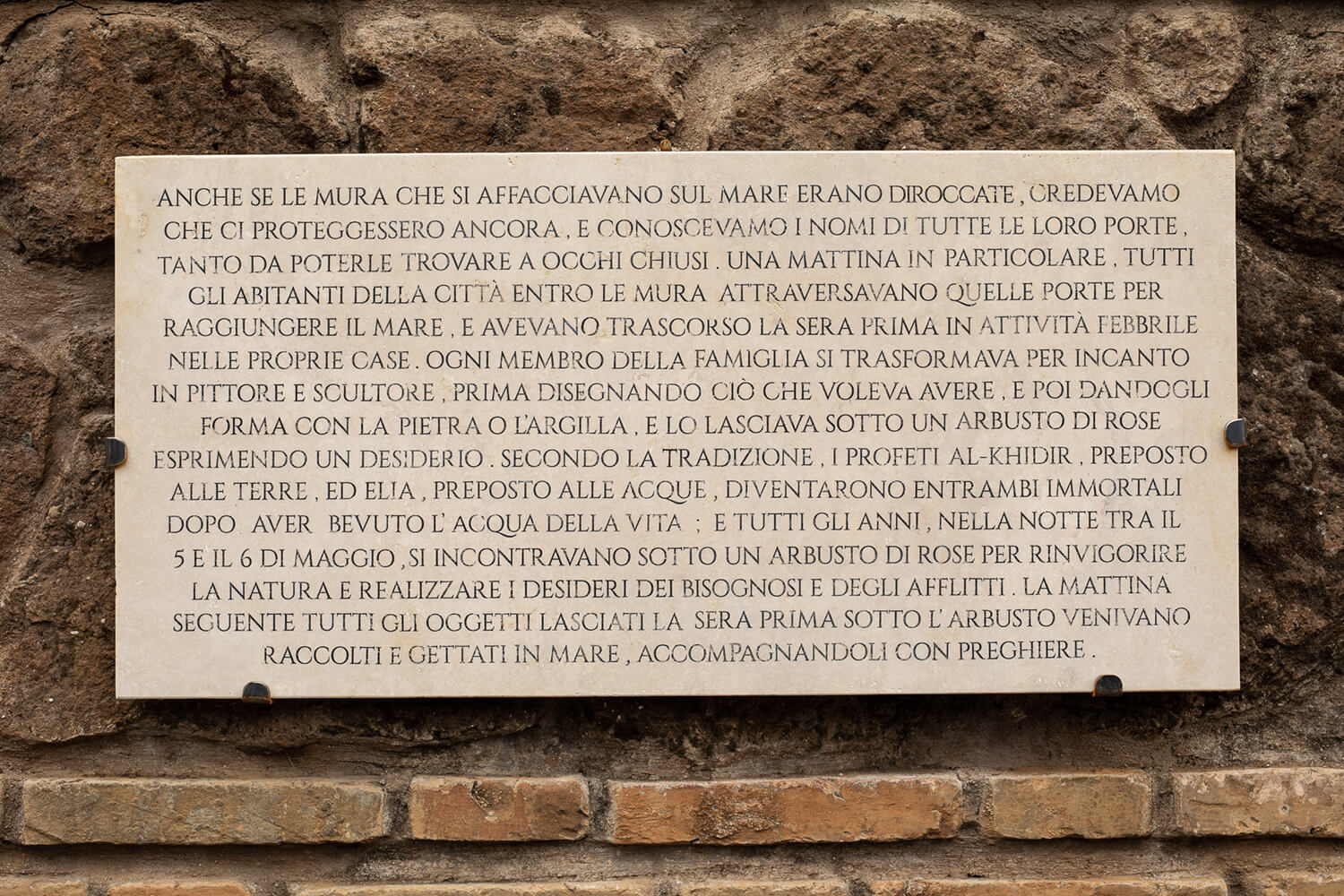

Al-Khidr

Even though the ancient city walls facing the sea were crumbling, we still believed they protected us, and we knew the names of all their gates so well that we could locate them even blindfolded. One morning, all the city’s inhabitants living within the walls passed through those gates to reach the sea; they had spent the previous evening engaged in feverish activity in their homes. As though under a spell, each family member would turn into a painter and sculptor: They would first draw what they wanted to have, then shape it with stone or clay and leave it under a rose bush all while making a wish. According to tradition, the prophets Al-Khidr, ruler of the lands, and Elijah, ruler of the waters, became immortal after drinking the elixir; and every year, on the night between the 5th and 6th of May, they meet under a rose bush to invigorate nature and fulfill the wishes of the needy and afflicted. The next morning, all the objects left under the bush the night before would be collected and flung into the sea, accompanied by prayers so that their wishes come true.

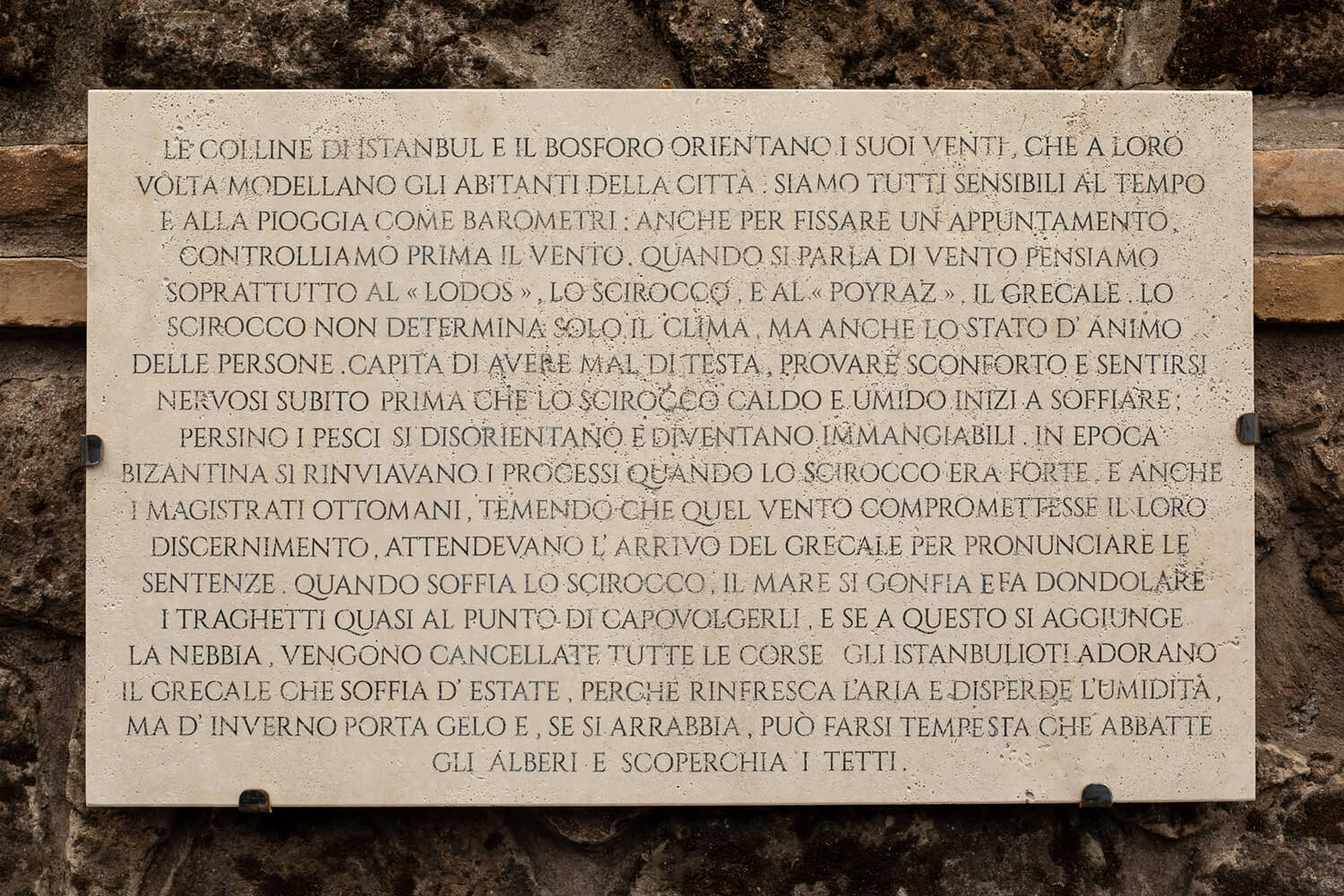

Wind

Istanbul’s hills and the Bosphorus steer the city’s winds, which, in turn, influence its inhabitants. Just like barometers, we’re all as sensitive to weather and rain: we even first check the wind before scheduling an appointment. When referring to wind, we mainly think of the Lodos, the Sirocco, and the poyraz, the Gregale. The Sirocco not only determines the weather, but also affects our moods. It is not uncommon for someone to have a headache, feel despondent, nervous and listless just before the hot, humid Sirocco starts to blow; even fish become disoriented and inedible. Back in Byzantine times, trials were postponed whenever the Sirocco raged, and Ottoman judges, fearing the wind could have impaired their discernment, would wait for the arrival of the Gregale before passing sentence. Whenever the Sirocco blows, the sea swells and shakes the ferries almost to the point of capsizing them, and if combined with fog, all sailings are cancelled. Fishermen refer to the Sirocco as the “stern” of the Gregale, and vice versa. Istanbulites love the Grecale that blows in the summer, for it cools the air and disperses the humidity. During winter, however, it brings frost, and if it rages, it can turn into a storm that knocks trees down and blows roofs away.

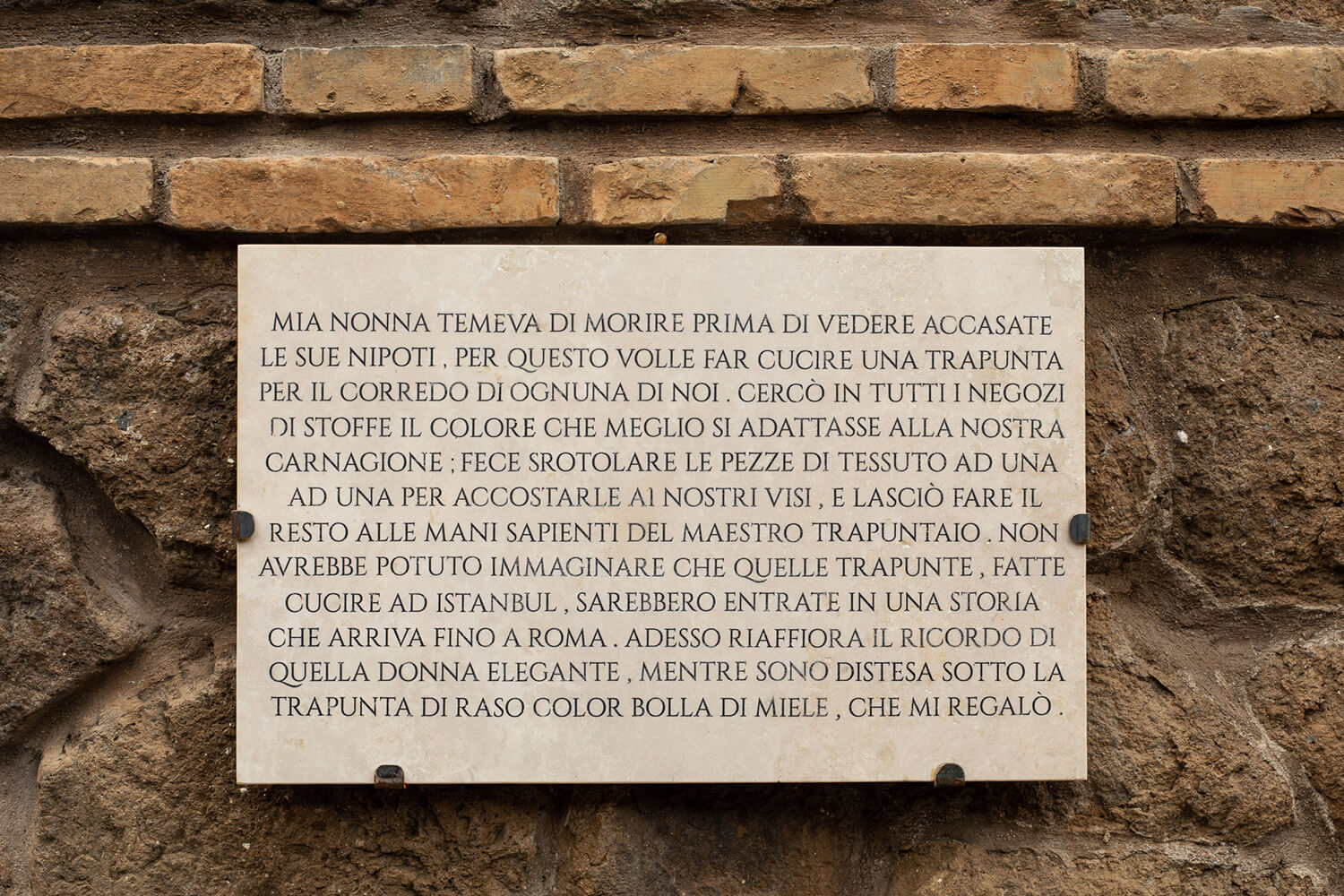

Quilt

My grandmother was so afraid that she would pass away before seeing her granddaughters get married, that she wanted to have a dowry quilt sewn for each of us. She searched through all the fabric merchants for the color that best matched our complexions, unrolling pieces of fabric one by one in order to bring them close to our faces, and left the rest to the skilled hands of the master quilter. Of course, she would never have imagined that those quilts, sewn in Istanbul, would become part of a story that stretches as far as Rome. Memories of that elegant woman resurface as I lie beneath her precious gift: the honey-bubble colored satin quilt.

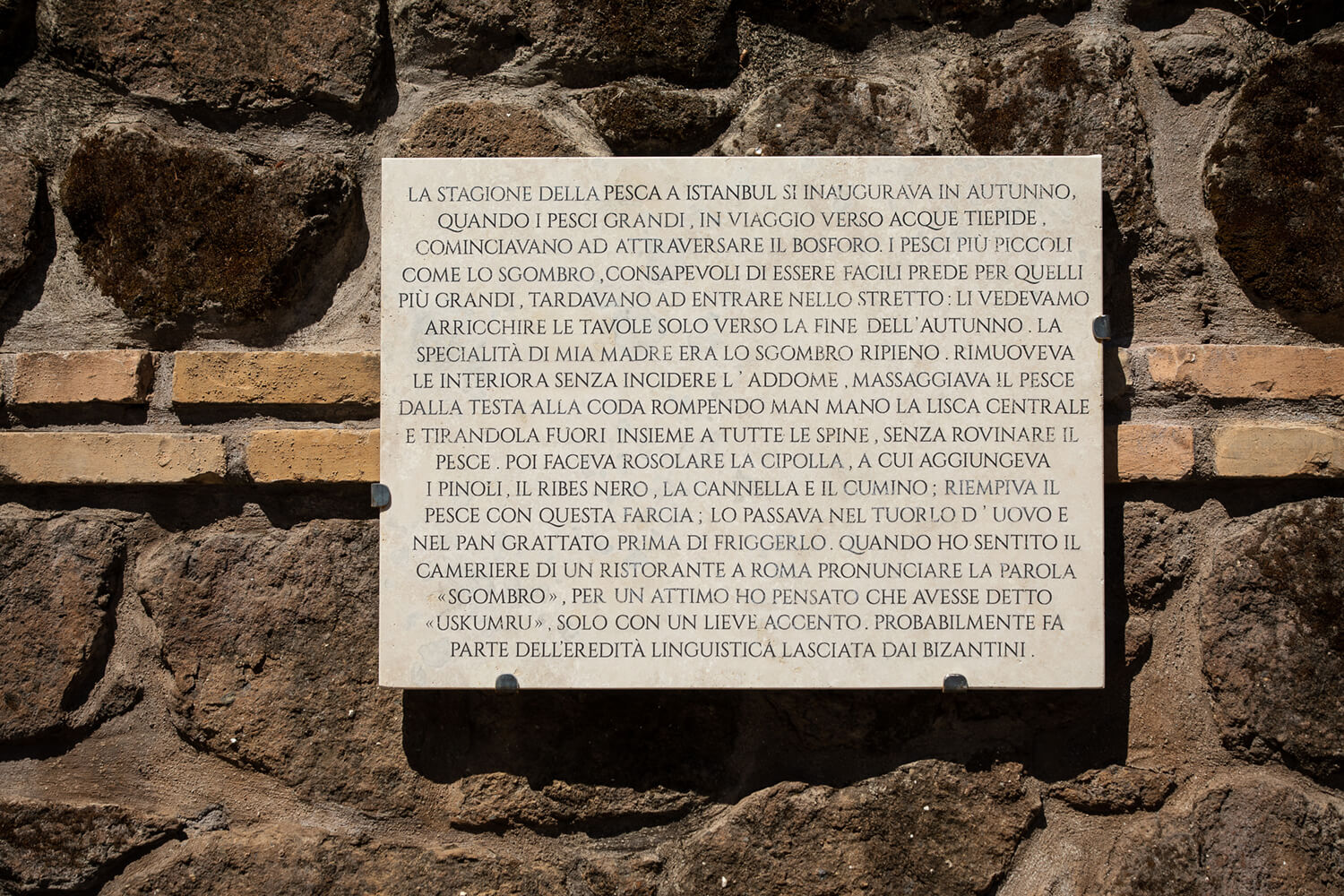

Uskumru

The fishing season in Istanbul would begin in autumn, when the bigger fish start to traverse the Bosphorus en route to warmer waters. Smaller fish such as mackerel, aware of being easy prey for the bigger ones, would delay their entry into the strait, and it was not until late autumn that we would see them gracing our tables. My mother's speciality was stuffed mackerel. She would remove its entrails without cutting through the abdomen, massage the fish from head to tail, breaking the central spine as she went along, removing it along with all the bones, without damaging the fish. Then she would pan-fry an onion, add pine nuts, blackcurrants, cinnamon and cumin, stuff the fish with this mixture and dip it in egg yolk and breadcrumbs before frying it. On hearing the waiter of a restaurant in Rome pronounce the word Sgombro, for a moment I thought he had just said Uskumru, only with a slightly different accent. It is probably part of the linguistic heritage bequeathed by the Byzantines.

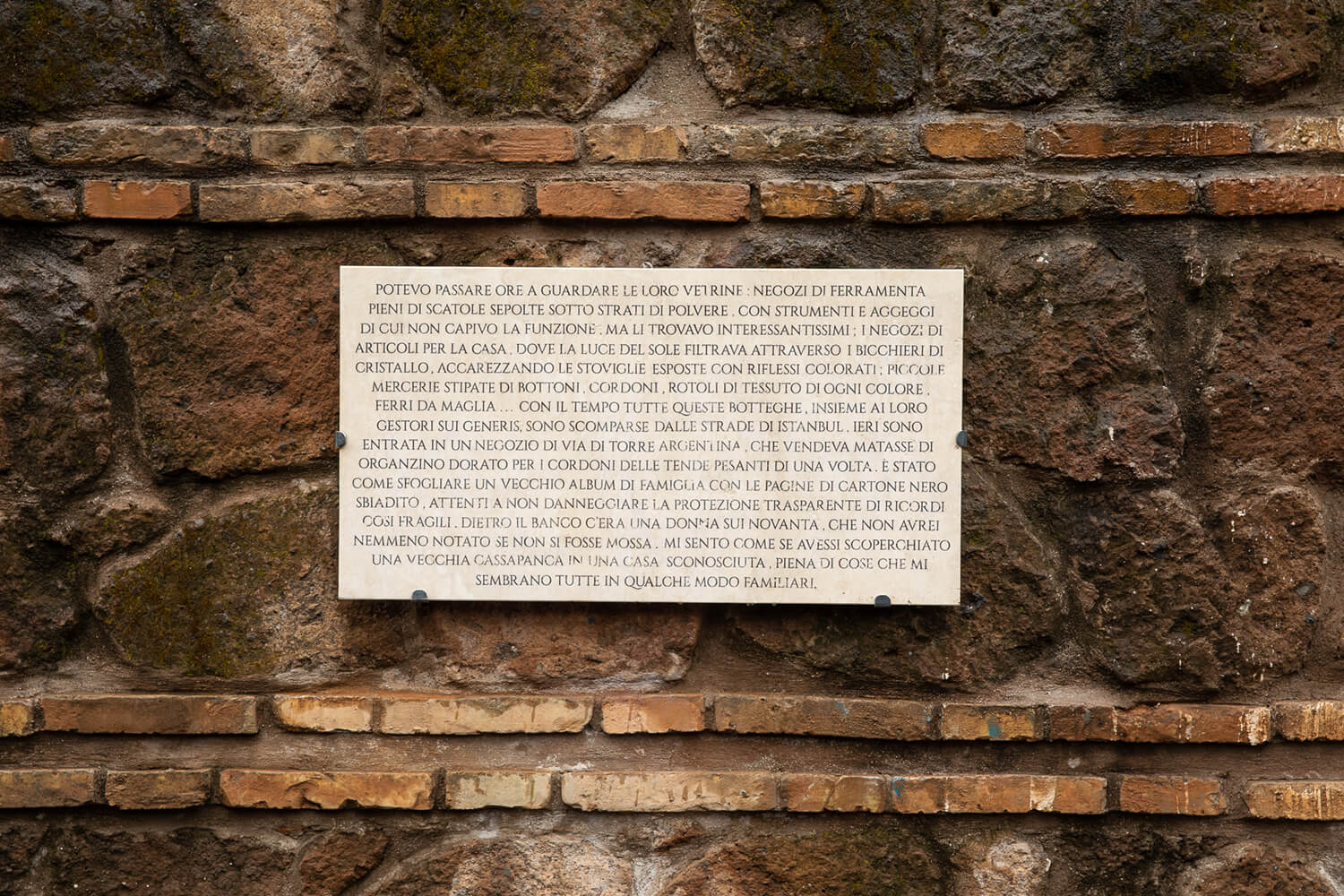

Haberdashery

I could spend hours gazing at their windows: Hardware shops full of boxes buried under layers of dust, with tools and gadgets I found fascinating although I didn’t really understand their function; homeware shops, where sunlight filtered through crystal glasses, caressing the dishes on display with colorful reflections; small haberdasheries crammed with buttons, cords, rolls of fabric of every color, knitting needles... Over time, all these shops, along with their one-of-a-kind owners, have vanished from the streets of Istanbul. Yesterday, I went into a shop here, which sold skeins of gold organzine for the cords of old-fashioned heavy curtains. I felt as though I was leafing through an old family album with faded black cardboard pages, careful not to damage the thin transparent sheet protecting such fragile memories. Behind the counter stood a woman in her nineties, whom I wouldn't have noticed if she hadn't moved. I feel as though I’ve uncovered an old chest in some strangers’ house, full of things that all seem somehow familiar to me.