2025, Installation

Developed for B-SHAPES, Borders Shaping Perceptions of European Societies, National History Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria

| / |

Starting with the emergence of post-Ottoman nation states in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, the project examined the associated processes of collective identity formation and the often painful dynamics that accompanied these developments.

Particular interest was paid to the artistic possibilities of making historical and contemporary events as well as long-term processes visible and legible, which are usually marginalised or completely ignored in the common European grand narratives.

Following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, parts of the archival material from the Ottoman period were sold to Bulgaria in 1931 for paper production at a price of 3 kuruş per okka (1,282 grams). Approximately 30 tons of documents, covering military, financial, political, legal, literary, and scientific-historical topics, were packed into bales at the Ottoman Archives building in Sultanahmet, loaded onto wagons, and transported to Bulgaria by train. When it became evident that the sold documents were not mere waste paper but significant archival records, the Bulgarian government confiscated them. Today, the National Library in Sofia holds the third-largest Ottoman archive in the world, after Turkey and Egypt, with over one million documents.

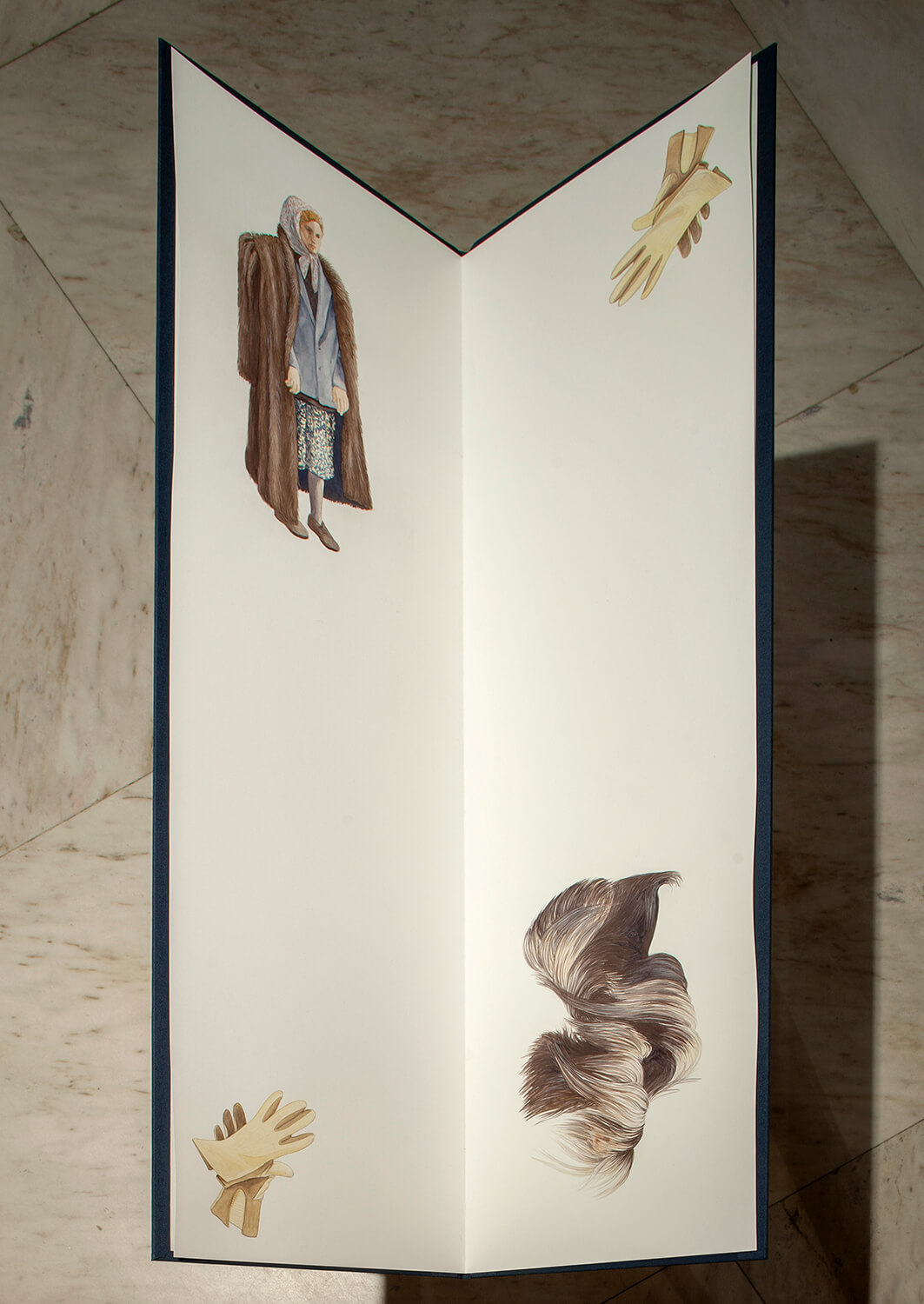

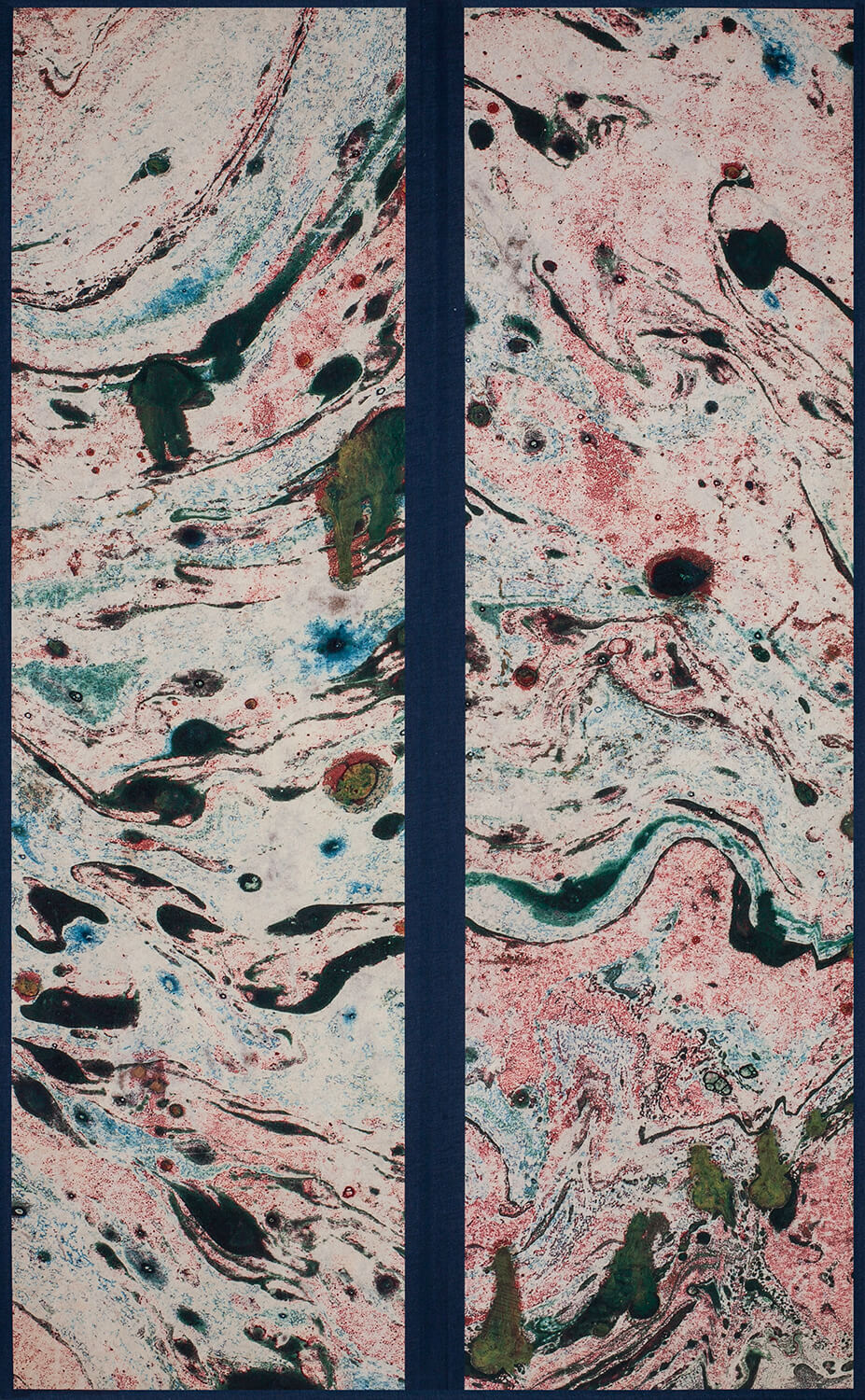

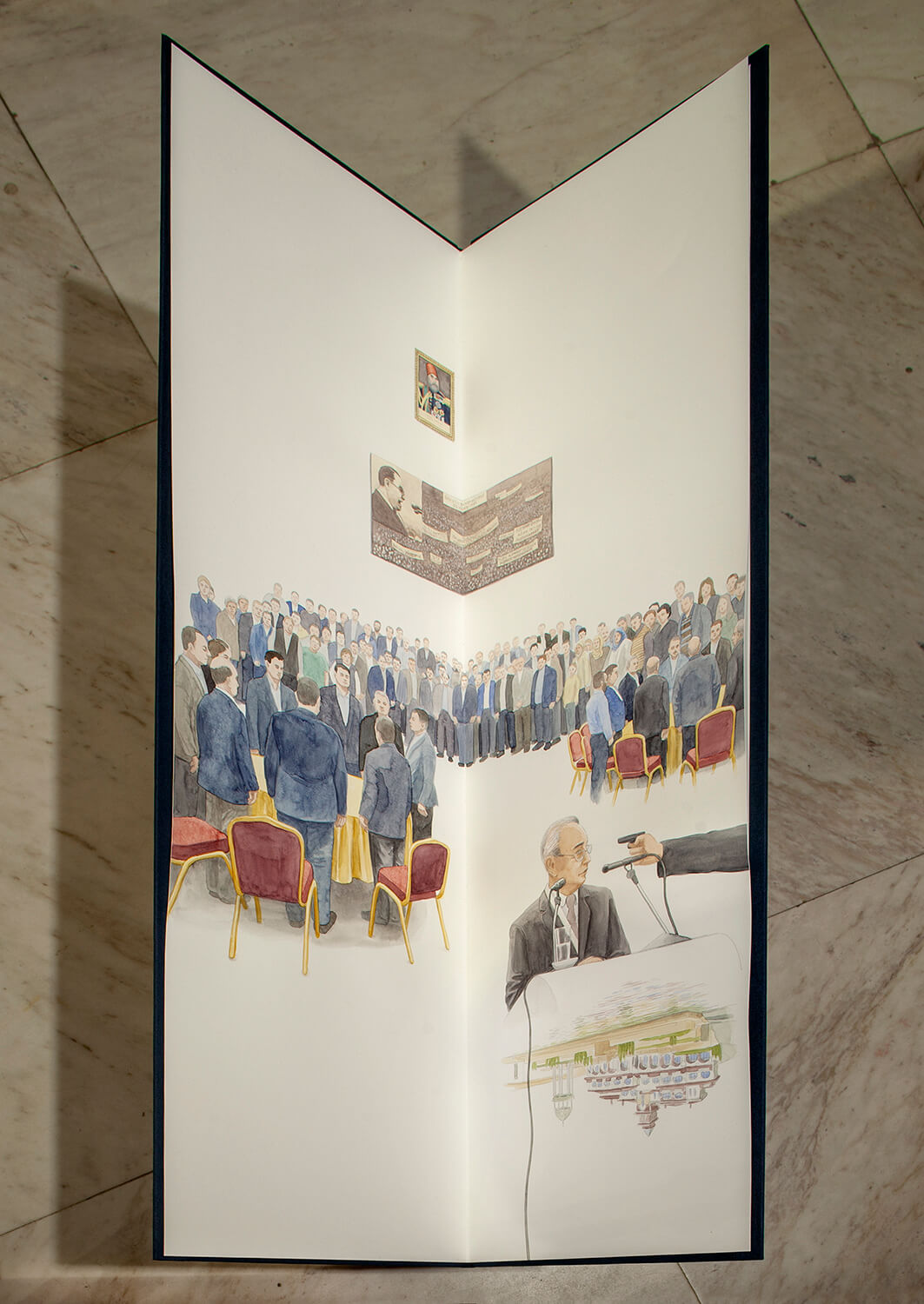

Ersen has studied the Sicil registers housed in the National Library in Sofia, which were maintained by Ottoman state officials. She has reproduced the covers of six of these registers, which are adorned with traditional Ebru paper (marbled paper), on a larger scale. Within the open registers, she presents drawings that depict narrative visual sequences, reminiscent of the narrative style found in miniature painting.

The registers, designed by Ersen under six distinct titles, are displayed in the National History Museum in Sofia, in the Great Hall of the former residence of head of state Todor Zhivkov. They are showcased on wooden frames in front of a wall mosaic of cultural significance to Bulgaria.

Radio Sofia

Although the Communist Party of Turkey was banned in 1927 due to its criticism of the Kemalist regime, it continued its activities underground. Facing increasing repression from the one-party regime, many socialist intellectuals fled Turkey and, after 1945, found a new home in communist Bulgaria. There, they were warmly welcomed by the Bulgarian Communist Party, which sought both to educate the Turkish minority and to support the banned communist movement in Turkey.

The renowned poet Nazım Hikmet, who was forced to flee Turkey due to his political beliefs and found refuge in the Soviet Union, collaborated with the Bulgarian Communist Party to promote the integration of the Turkish minority into the socialist system. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, and magazines, he shared his ideas on how targeted propaganda could reach the Turkish population. To this end, he participated in numerous events organized by the party for the Turkish community.

During the Cold War, broadcasts from "Radio Sofia" and Bizim Radyo (“Our Radio”) in Leipzig, which were transmitted in Turkish, were listened to not only by committed socialists but also by the broader population. For example, a Turkish guest worker in West Germany used Radio Sofia to stay in touch with his wife, whom he could not bring to Germany. Tenzile, from Samsun, tuned in to the radio every day at the same time to hear the song that her husband Ahmet had requested for her from Berlin.

Ghostbusters

In islamischen und türkisch-islamischen Staaten wurden die eroberten Gebiete und errungenen Siege durch Briefe und Erlasse bekanntgegeben, und die historischen Werke, die diese Eroberungen beschrieben, wurden als „Zafername“ (Siegeschroniken) bezeichnet.

Im Hintergrund des Bildes, das Ersen als „Ghostbusters“ bezeichnet, wird ein Schlachtfeld abgebildet, das von diesen Miniaturen inspiriert ist.

Heute dient die Grenze zwischen Bulgarien und Griechenland zu Türkiye gleichzeitig als Bollwerk zum Schutz Europas. Die Flüchtlinge, die versuchen, diese politischen Grenzen zu überwinden, werden in Europa als Bedrohung für die wirtschaftliche, soziale und politische Stabilität angesehen und von rechtspopulistischen Politikern, die weit entfernt von der Grenze agieren, als kulturelle Vorhut eines historischen Feindes betrachtet.

In den Istranca-Bergen patrouilliert eine Gruppe vermummter Personen in Tarnkleidung mit Skimasken, bewaffnet mit langen Messern, Bajonetten und Schlagstöcken, auf der Jagd nach Flüchtlingen. An den Emblemen auf ihren Uniformen, die einen Wolfskopf zeigen, umrahmt von kyrillischen Schriftzeichen, erkennt man, dass sie Mitglieder der paramilitärischen Gruppe „Bulgarische Nationale Bewegung Schipka“ sind. Die paramilitärische Gruppe hat ihren Namen von den Kämpfen am Schipka-Pass, bei denen russische Truppen mit Unterstützung bulgarischer Freiwilliger im Balkangebirge gegen das Osmanische Reich um die Kontrolle über den Schipka-Pass kämpften. Über all dem wacht der Beschützer dieser Szene, bereit, böse Geister zu vertreiben.

The memory of the river

At the start of the new year, Orthodox Christians in Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria process to rivers, lakes, or the sea. To perform a ritual commemorating the baptism of Jesus and warding off evil spirits, priests bless the waters and cast a cross into them. The faithful, diving into the cold water to retrieve the cross, share the hope that its finder will be blessed with good fortune.

The Evros River, also known as Mariza or Meriç, marks the southeastern external border of the EU at the Greek-Turkish and Bulgarian frontier, standing as one of Europe’s most heavily guarded borders. Until recently, it was the cheapest but most dangerous land route for illegal immigrants entering the EU. Steeped in mythology, this river was the stage for a tragic tale: the Maenads of Dionysus beheaded Orpheus and cast his head into the Meriç, from where the singing head drifted to the island of Lesbos, its voice echoing through the waters of the Mariza.

In retellings of mythological scenes, Orpheus returns time and again to this modern border—this time in the guise of an ill-fated smuggler. The journey to Europe becomes a crossing of the Hades, that river which, in ancient mythology, marked the boundary to the underworld.

The Greek 2-euro coin depicts a scene from a 3rd-century AD mosaic discovered in Sparta. It portrays the abduction of Europa—the mythological figure after whom our continent is named—by Zeus in the form of a bull.

Madonna in a Fur Coat

In the early 1950s, American photographer Jack Burns travelled on the Orient Express from London to Istanbul to create a series of photographs for LIFE magazine. During a stop at Kırkağaç station in Edirne, a group of women wearing fur coats caught his attention. His impromptu photographs capture the tragedy of these Turks forcibly deported from Bulgaria. The deportees were not permitted to take jewellery or cash with them. As a result, families invested their savings in fur coats, which the women wore across the border. Upon arriving in Turkey, the furs were sold to help meet the families’ basic needs. For the women, these coats often served as protection from the cold for only a few days before becoming a means of survival.

In Ersen’s drawing, which resembles a playing card, a woman in a fur coat stands in one corner, while in the opposite corner, a Kukeri figure adorned with long fur dances to ward off evil spirits. In the remaining two corners of the drawing, a remarkable item from the collection of the National History Museum in Sofia is depicted: a pair of gloves that belonged to the poet Elisaveta Bagryana. She was one of the authors of the Bulgarian national anthem used between 1950 and 1964.

*The title of the work derives from the novel by Sabahattin Ali. He was born in 1907 in Eğridere (now Ardino, Bulgaria). At the school where he taught German, he faced an investigation for allegedly disseminating communist propaganda. He was arrested due to a poem in which he criticised the policies of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. During the Second World War, his books were banned and publicly burnt. Following his release from prison, he travelled to Edirne. However, his true aim was not to remain there, as he told others, but to escape to Bulgaria via Edirne to avoid another arrest for political reasons. Near the Turkish border crossing, he was killed by his smugglers. Given the author’s critical stance towards government policies, it is suspected that the murder was carried out on the orders of the secret police.

Association

The first major wave of migration from the Balkan countries towards Turkey began with the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 redrew the political and administrative map of the Balkans. Extensive migration flows brought about profound changes in both the Ottoman Empire and the demographic composition of the Balkan nations. These migratory movements persisted until the final quarter of the 20th century.

People living as minorities in the Balkans, due to their faith or ethnic origins, faced increasingly systematic assimilation policies. The identity politics of later communist regimes, which aimed to create homogeneous societies, intensified these repressions. Names were forcibly changed, the use of the Turkish language was banned, and Turkish-language educational institutions were shut down. Clothing, religious practices, and freedom of worship were heavily restricted, and places of worship were closed. Those who resisted assimilation were deported to the notorious Belene concentration camp, where they endured torture, punishment, and dispossession. Many were compelled to emigrate.

Over the years, those who had been oppressed and forced to migrate established immigrant associations in Turkey to preserve their cultural values and pass them on to future generations. These associations bolstered the socio-economic solidarity of the community and ensured their concerns were heard in the public sphere. They worked to understand, protect, and expand their rights, as derived from national laws and international agreements.

Today, Balkan migrants form a significant part of Turkish society and are regarded by political parties as a key voter base. Ahead of elections in Turkey and the Balkan countries, these associations are frequently visited by political representatives.

Ersen depicts such a visit and also two photographs hanging on the walls of the association's offices. The first photograph captures a speech by Mümin Gençoğlu, the chairman of the association, originally from Kardzhali in southern Bulgaria. It was taken during a demonstration in Bursa on 20 April 1985, known as the “Protest Rally Against Bulgarian Oppression,” which drew 100,000 participants.

The second photograph shows Osman Nuri Pasha, a commander of the Ottoman Army who led the defence of Plevna during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877.

Dervish

The Tasavvuf-Tarikat, or mystical Sufi orders, established Tekkes—places where members lived, worshipped, and performed their duties. These were constructed in a distinctive architectural style and comprised various areas, including rooms for dervishes and guests, mausoleums of prominent order leaders, libraries, kitchens, bathhouses, and other facilities.

During the Seljuk and Ottoman eras, such Tekkes, often functioning as charitable foundations (Vakıf), were typically built along major trade routes. They encompassed extensive farms, vineyards, gardens, and lands. Beyond housing order members, they provided free accommodation for passing travellers. Meals prepared in the Tekkes were distributed to guests and needy families in the surrounding areas.

The introduction of Islam to the Balkan region was not solely through warfare. As early as the late Byzantine period, Sufi dervishes who settled in the region played a significant role. They built Tekkes in remote, fertile areas outside cities, bringing their culture with them. Guided by principles of tolerance and selfless service, they approached people regardless of religion or language, earning the goodwill of non-Muslim communities as well.

The Tekkes and their leaders, the Sheikhs, shaped not only religious, social, and cultural life but also played a central role in political and economic organisation. They significantly contributed to the expansion of political boundaries, the cultivation of newly acquired territories, and the settlement of populations.

The Ottoman Empire encouraged the settlement of Bektashi Turkmen in the Balkans, as their open-minded attitude positioned them as mediators between local populations and Ottoman authorities. Traces of the Bektashi remain visible today. Their Tekkes are visited not only by Muslims but also by Christians. A notable example is the hexagonal building with a lead roof surrounding the tomb of the 16th-century Bektashi cleric Ak Yazılı Baba. For Alevi Muslims in the Balkans, it is a sacred site, while Christians revere it as the tomb of Saint Athanasius, who, according to tradition, was martyred by the “Turks” for his faith. Both communities share a common ritual: they light candles, circle the tomb three times, and toss coins into a small opening at the head of the tomb. Muslims and Christians alike believe that those who can pass their hands through this opening will have their sins forgiven.